Intro to a Simple Path and Activity Planner

By Cameron Pittman, Viraj Parimi, Alisha Fong, and Brian Williams. It takes approximately 30 minutes to complete this lesson.

Imagine you're a software engineer and a firefighter. Your department bought a set of firefighting aerial drones that can pick up water and drop it on fires. With your knowledge of firefighting and model-based autonomy, you want to program the drones to autonomously fight fires in remote locations that would otherwise be dangerous or difficult for humans to extinguish.

We'll call this the simple agent and spend the next few lessons building it from scratch using algorithms and techniques from model-based autonomy.

The Firefighting Problem

Let's make the firefighting problem more concrete.

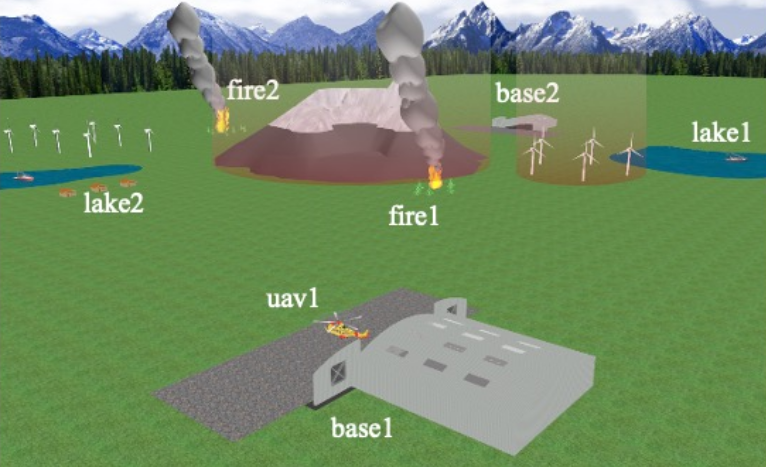

The firefighting problem involves putting out two fires, fire1 and fire2. Each fire can be

extinguished by dropping water over the fire using an unpiloted aerial vehicle (UAV), uav1. uav1

is housed at a base, base1. Two lakes, lake1 and lake2, are available to pick up water. The

UAV needs to avoid flying into a mountain and the two wind farms that you can see in the image

below.

A UAV has commands for taking off and landing, flying between locations, picking up water, and dropping water. In order to put out a fire, the UAV needs to drop water from a high altitude then a low altitude.

The problem starts with fires raging at locations fire1 and fire2, while the uav1 is located

at base1 with an empty water tank.

Your goal is to extinguish the two fires and to have uav1 return to the base. Its solution, and

what your agent should produce, is a sequence of commands that bridges the start and goal states.

In pseudo-code, you could define the following classes and methods to model the problem space.

class Location class Fire(Location): Location location bool had_high_altitude_water_dumped bool had_low_altitude_water_dumped bool is_burning class Lake(Location): Location location class UAV(Location): bool is_flying bool has_water Location current_location def take_off() def land() def fly(Location) def pick_up_water() def dump_water_low() def dump_water_high()

Think about this scenario. What sequence of commands would you string together to put out both fires?

The Traditional / Brute Force Method

As a human planner, you could reason through this specific problem and figure out a solution. Here's what it could look like:

uav1.take_off() ## fight fire 1 # high altitude pass uav1.fly(lake1) uav1.pick_up_water() uav1.fly(fire1) uav1.dump_water_high() # low altitude pass uav1.fly(lake1) uav1.pick_up_water() uav1.fly(fire1) uav1.dump_water_low() ## fight fire 2 # high altitude pass uav1.fly(lake2) uav1.pick_up_water() uav1.fly(fire2) uav1.dump_water_high() # low altitude pass uav1.fly(lake2) uav1.pick_up_water() uav1.fly(fire2) uav1.dump_water_low() ## return to base uav1.fly(base1) uav1.land()

You can get a sense for the size of the solution space with a little bit of analysis of the sequence that we found.

While you solved this specific firefighting scenario, you haven't made the all-purpose autonomous aerial firefighter that you set out to build. What if there were three fires? What if you had two UAVs at your disposal? What if there was only one lake? What if the drone had more complicated flying commands? The solution above doesn't even factor in the mountain and wind farm obstacles in the flight path.

Writing bespoke solutions for each possible permutation of the problem is clearly not the most effective way to solve this problem, nor is enumerating all possible sequences of actions and testing them to see if they work. We'll spend this set of lessons building a smarter planner that can quickly reason through problem states and constraints to produce path and motion plans.

Components of a Simple Planner

Over the course of the following lessons, we'll build a simple executive with two planners:

- An activity planner to decide what to do to satisfy goals

- A motion planner to decide where to go to satisfy goals

As input, we'll provide:

- states that represent the world

- a model of the actions our agent can take and how they affect states

- the initial state of the world and our agent

- the goal state of the world that we'd like our agent to achieve

As output, we expect our simple planner to provide a sequence of actions to satisfy all the goals, which would also include any motion plans if the agent needs to move in the process.

There are many ways activity and motion planners can work together. At a high level, our aim will be for the activity planner to decide when motion to a location is necessary, at which point it will ask the motion planner to map a route from its current location to the new location. Using a processing model as an analogy, if the activity planner is the main thread of our program, then the motion planner is a subroutine.

Key to solving this planning problem is writing a program that can reason about states, or information about the agent and the world. In order to do so, we need to formally define state space programs.

State Space Programs

A state space program is used to specify the states, operators, initial state, and goal state of a state space search problem.

Object-oriented languages can be used to model state space problems. Python is one such object-oriented language. In Python, objects have associated properties and methods. Properties are variables that can take on one of a finite set of possible values, while methods may enact changes in objects. Let's transform the pseudo-code we saw before to Python to see a state space program in action.

## define Python classes that model the state space problem class Location: """ Describes a location on Earth """ def __init__(self, latitude, longitude): self.coordinates = (latitude, longitude) class Fire(Location): """ Fires burn at a location and can be partially or completely extinguished """ def __init__(self, latitude, longitude): super().__init__(self, latitude, longitude) self.had_high_altitude_water_dumped = False self.had_low_altitude_water_dumped = False @property def is_burning(self): """ Convenience method to check if the fire is still burning As a `@property`, we can use `is_burning` as a normal property instead of a method, eg. `uav1.is_burning` """ return not (self.had_high_altitude_water_dumped and self.had_low_altitude_water_dumped) class Lake(Location): """ A body of water at a location """ def __init__(self, latitude, longitude) super().__init__(self, latitude, longitude) self.location = location class UAV: """ An unpiloted aerial vehicle """ def __init__(self, location): # call it a "current" location because a UAV's location can # change self.current_location = location self.is_flying = False self.has_water = False def take_off(self): """ Fly up from the ground straight up into the air """ if not self.is_flying: self.is_flying = True def land(self): """ Fly straight down from the air to the ground """ if self.is_flying: self.is_flying = False def fly(self, location): """ Move to another location. UAVs need to be in the air to move """ if self.is_flying: self.current_location = location def pick_up_water(self, lake): """ Store water in the UAV """ if self.current_location == lake.location: self.has_water = True def dump_water_low(self, fire): """ Drop water on a fire from a low altitude """ if self.current_location == fire.location and self.has_water: self.has_water = False fire.had_low_altitude_water_dumped = True def dump_water_high(self, fire): """ Drop water on a fire from a high altitude """ if self.current_location == fire.location and self.has_water: self.has_water = False fire.had_high_altitude_water_dumped = True ## instantiate the objects of the problem in their initial states base1 = Location(0, 0) fire1 = Fire(1, 1) fire2 = Fire(2, 2) lake1 = Location(3, 3) lake2 = Location(4, 4) # instantiate the UAV at its home base uav1 = UAV(base1)

The state space of the problem is defined by all assignments to the properties of all object instances.

In this example, a UAV has the variable current_location as a property, which can take on the

value of one of the locations, such as base1, fire1, fire2, lake1, lake2 and so forth. The

UAV also has two boolean variables as slots, is_flying and has_water, which describe the

current state of the UAV.

Methods are defined over these objects. We specify six primitive methods above, which correspond to

the six UAV commands (not counting __init__, which is a Python constructor). Each primitive

method specifies operators of the state space problem.

Looking through the Python, you'll notice a pattern in the primitive methods. Each one includes a

clause (usually an if-statement conditional), and an effect. Clauses and effects use and act

on the states of the objects. They take the form of:

def primitive_method(): if clause: apply effect

Another way of looking at it is that the primitive methods specify (1) the states in which each

method applies, and (2) the states that result from applying each method. If (1) does not evaluate

to True, then we cannot modify states as per (2). The clauses and effects of a state space problem

should model the rules of logic and physics of whatever problem is being solved. Using both of the

UAV's dump_water methods as an example, the location checks are necessary because a UAV cannot

drop water over a fire if it is not physically above it. Similarly, a UAV cannot dump water on a

fire if its water tank is already empty!

There are some aspects of the Python representation of the firefighting problem above that require further thought. Read through the code carefully and then check your intuition with the following questions.

fly method does not compare the UAV's current location to the intended destination in its clause. Why? Is this a bug? In other words, is it a problem that fly will apply its effect even if the UAV is already at the intended destination?

fly's clause if you wanted to. However, it is not necessary because the end result is the same regardless. You may be tempted to think of fly as meaning the UAV has to change location. Instead, think of fly's purpose as enforcing the end state of the effect. Another way of saying this is that, as a primitive method in a state space problem, fly's only responsibility is guaranteeing the UAV is in a location when the method is done executing. Whether the UAV starts at that location or somewhere else doesn't matter. So, no, this is not a bug.

If fly is going to perform its job of ensuring the UAV ends up at a given location, it will

certainly need to call a motion planner to plot a safe path.

What about landing?

land operator?

if self.current_location == base1 to be safe.

Our representation of the firefighting problem relies on the Location class to describe where

objects are. We use latitude and longitude to define locations. There are implications with this

representation we would need to deal with in reality.

We originally said that a state space problem should include initial and goal states. The initial states were provided in the Python code. How about the goal states?

not fire1.is_burningnot fire2.is_burninguav1.current_location == base1

Defining the right goal states is key to ensuring your autonomous system exhibits the behavior you want.

Coming Up Next

We saw before that the combinatorial nature of state space problems leads to exponentially huge solution spaces, even when the solution was limited to activity planning (ie. we never tried to actually plot a safe route between lakes and fires). Expanding the solution space to one where we also have to navigate a vehicle with complex dynamics over terrain and around obstacles, all while managing fuel resources, will further exacerbate the seemingly intractable problem of trying to pick a safe activity and motion plan from an endless sea of alternatives.

The good news is that computer science and model-based autonomy exist. We have a huge range of techniques to reduce the size of state spaces and quickly find safe solutions. Namely, search is a foundational component to any autonomous program, and will be core to our simple activity and motion planner.

Over the next few lessons, you'll have a chance to explore the fundamentals of search algorithms. You'll start with uninformed search, or systematic search without taking advantage of the problem domain, and from there you'll learn informed search, or search using heuristics that guide programs to optimal solutions faster.

One More Thing: Reactive Model-Based Programming Language

The Reactive Model-based Programming Language (RMPL) is a language for programming autonomous agents. RMPL uses the metaphor of state-space search, to model agent behavior and to specify goal behavior at an abstract level.

The MERS lab (who wrote these lessons) uses RMPL to model state space programs. Take a look at our introductory lesson to RMPL here.